The EU may be forced to water down its ambitions for corporate transparency on climate change to keep the U.S. on board with a global deal. The idea is to require large companies to disclose green information with the same rigor and external checks as they do for financial disclosures. [EU’s ambitions on climate disclosures run up against US wall – Politico]

As heatwaves and droughts grip the continent this summer, the EU is pursuing a plan within its own borders to overhaul how companies report on climate change, also providing a clearer picture to their investors of the potential threat global warming could pose to the business.

EU lawmakers and capitals agreed a deal in June that will require 50,000 companies based in the bloc to publish information on their environmental footprint as well as on the potential impact climate change could have on their operations. The deal will eventually encompass foreign companies operating within the bloc.

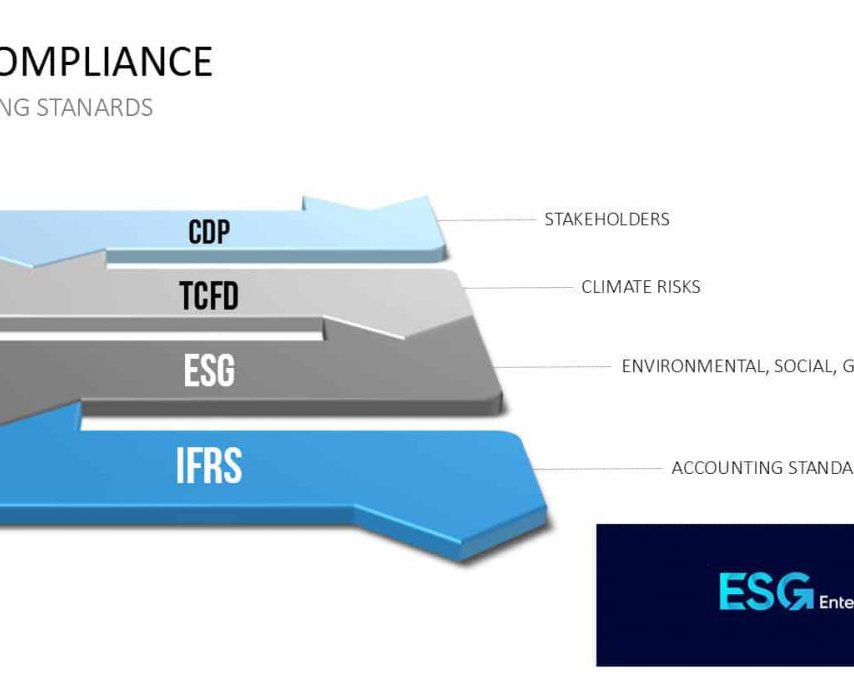

Brussels is now working on the detailed standards that will underpin those disclosures covering climate change, pollution, water and marine resources, biodiversity, the circular economy, social and governance issues — via an accounting body called the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG).

It's a topic that is also gathering momentum internationally as governments step up their efforts to combat climate change and drive more money into green projects.

Yet, while the EU may want to lead the way globally on green disclosures, it is also finding itself increasingly isolated.

That’s because at the heart of the EU’s plans is the concept of “double materiality” — where companies need to not only report on the core financial impact that climate change could wreak on their business, but also on their own environmental and societal footprint.

It’s a fundamentally different vision to the one now being pursued by a key international standard-setting body — where climate disclosures will be more strictly linked to a company’s bottom line.

The work by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), set up in the wake of the COP26 climate conference, aims to create a “global baseline” on climate disclosures that can then be built on by each jurisdiction.

EU inspiration

The difference in approach means that for some, the EU should push harder to get the ISSB to incorporate its vision.

“The European Union is not the only power involved in drawing up new non-financial standards. If others prevail, then sustainable development would be defined by a non-European vision, making it more difficult for European values to be effectively taken into account,” said Pascal Durand, a French EU lawmaker, who led work on the reporting legislation in the European Parliament.

As well as the divide on double materiality, the MEP for the centrist Renew Europe group pointed to the lack of global standards to cover biodiversity, social and human rights factors “which are values important for European policy-makers.”

NGO Finance Watch has also called on the global standard-setter to go beyond the “outside-in” approach and "embed the double materiality principle in the global baseline."

The EU’s markets regulator, too, has warned that the global standards need to define better how companies should evaluate and disclose their impact on the environment — to make sure the global and EU versions can knit together.

An EU official said the bloc supports the ISSB's objectives but the "narrower financial materiality reporting objective of the ISSB and the so-far limited coverage of sustainability issues (only climate-related reporting) mean that ISSB standards cannot fully meet the EU’s needs or ambitions."

"From the Commission’s perspective, the ambition is high on developing sustainability reporting standards including through cooperation with major partners such as the U.S.," the official said, noting however that the "EU plans to be even more ambitious at home and is ready to inspire other jurisdictions."

US realism

But for others, it’s time for the EU to be realistic about where the rest of the world stands.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for instance is working on its own plans for climate disclosures — which would require big listed companies to publish information on their greenhouse gas emissions and how climate change is affecting their business.

But that's only when those disclosures fit within that tighter definition of being "material" to a company's financial standing. That more limited approach is more in line with the ISSB's proposals but has also proven controversial with some of corporate America.

Eelco van der Enden, chief executive at the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) — the standard-setting organization which developed the concept of double materiality — said he doesn’t see the U.S. going for double-edged disclosures within the next 25 years.

“It's not in the nature and the culture to make that mandatory,” he said. Still, the Dutchman said U.S. regulators could tell companies to use his organization's standards on a voluntary basis if they want to go further in their public reporting.

Van der Enden called for “political willingness” to try and reach as much alignment as possible at an international level, which he described as being able to “step over your own shadow and understand that it's not only about your constituency.”

“If you want to achieve something, you also should take into account the interests of some of the other constituencies,” he said. "The winner gets it all is the wrong approach in the field of sustainability."

Otherwise, van der Enden said, the risk is that the EU, international and U.S. standard-setters all “go their own way” as well as other large jurisdictions like Brazil, China, India and southeast Asia.

“You don't want to have different concepts and different data out there that are incomparable, because literally no one benefits from that,” he said.

Global investors are also worried the EU could move too far on its own path from any international agreement.

“You don't get a gold medal for being first if you're in a different race,” said Eric Pan, chief executive of the Investment Company Institute, which represents fund managers.

“The EU obviously can add on top of the ISSB. Nobody is arguing that the EU should be constrained,” he said. “We’re just saying, think about this as a global problem. This is a common challenge for a lot of different jurisdictions, so to the extent possible, try to build off of these multilateral standards.”