A survey by the Leather Apex Society of East Africa, which is seeking to establish leather quality infrastructure in the East African Community (EAC), finds a sector that is bubbly with optimism and rich material base even as it is held back by low uptake of technology and inadequate supporting policies. [Policy tweaks that can raise leather production in EAC- Business Daily]

Leather is one of the most traded agro-driven commodities in the world. At an estimated annual market value of Sh22.8 trillion (USD 200 billion), leather’s revenues are higher than those generated from coffee, tea, rice, rubber, cotton, and sugar combined.

Yet East Africa’s share of this pie is a paltry 0.24 percent or Sh54.6 billion (USD 478 million) with its contribution to the East African Community (EAC) Gross Domestic Product a mere 0.28 percent, according to the regional bloc’s Leather Strategy Implementation Roadmap for 2020-2030.

This miniscule contribution runs counter to another reality: that East Africa’s leather sector sits on a rich raw material base, playing host to three percent of the world's total bovine herd, five percent of the goats and two percent of the sheep.

The strategy, referred to above, identified several obstacles, key of which is the absence of defined production standards.

A survey by the Leather Apex Society of East Africa, which is seeking to establish leather quality infrastructure, finds a sector that is bubbly with optimism and rich material base even as it is held back by low uptake of technology and inadequate supporting policies.

A desk study and conversations with industry players and experts across the six EAC members reveals a weak policy environment that discourages investment in value-added products such as footwear and leather goods.

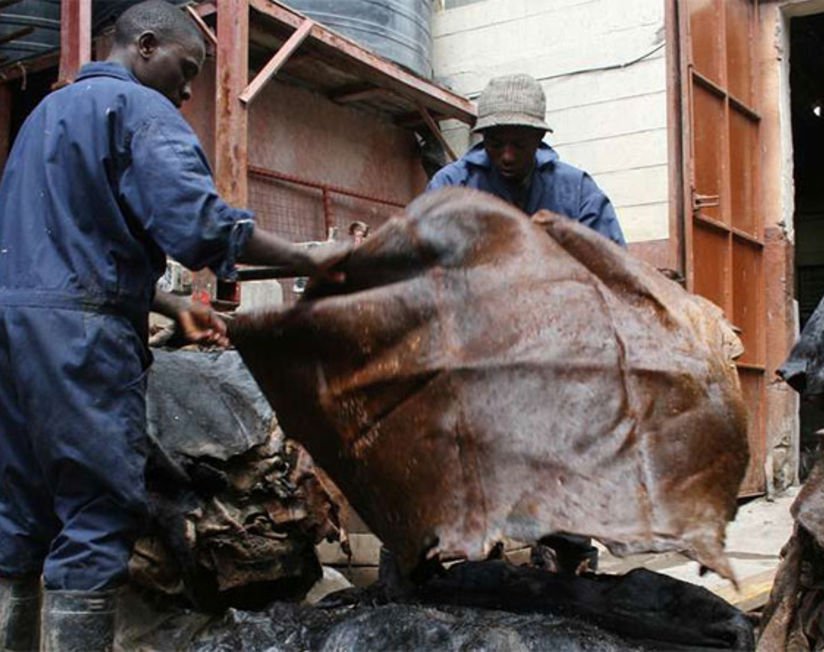

Continued export of critical raw materials such as hides and skins as well as wet-blue (moist chrome-tanned leather that is blue in colour) are some of the challenges.

Weak institutional arrangements to enforce quality standards in the value chain, as well as slow pace of harmonisation of standards across the region, are other impediments.

The high cost of leather production is yet another obstacle. This is attributed to costly electricity, labour, space, accessories, tanning chemicals, and machinery required for globally accepted products.

The Kenyan government recently crafted a plan to cut the cost of electricity by 30 percent by the end of this year’s first quarter. It has already cut it by 15 percent, but investors in the industry say much more needs to be done to reduce costs further.

“There is a need to strengthen the Kenya Bureau of Standards and improve coordination between it and the Anti-Counterfeit Agency for stricter enforcement of quality,” said Yasin Awale of Sagana Tanneries.

Inconsistent quality

In Tanzania, poor appreciation of quality in the leather value chain, owing to skills gap is a major concern.

“We have a grading for hides and skins and the Tanzania Bureau of Standards [TBS] is doing a decent job, but people do not follow the standards. There is need for more awareness on the importance of these standards,” said Freddie Kabala, the project coordinator of the Tanzania Leather Association.

In Uganda, the story is more or less the same with manufacturers citing inconsistent quality of leather, which they mostly import from neighbouring countries.

“Most players cannot afford to buy the best quality first-class skins and hides,” said Moses Amooti, the managing director of Amooti Leather Company in Kampala.

In Burundi, the industry grapples with outdated equipment and technology, poor skills, and low skills transfer as well as inadequate collaboration amongst value chain agents.

There is also no national system certification body, leaving foreign entities to conduct such services at the expense of the government.

In Rwanda, a multi-agency task force on leather, bringing together the Rwanda Agricultural Board and Rwanda Standards Board, among others, seeks to create an environment in which clean technologies will be adopted along the whole value chain from better livestock keeping to the finished products.

Overall, in EAC the drive for quality and standards has not taken root in the informal sector and rural areas where the raw materials originate, with capacity enhancement tending to focus on the formal sector.

This limits skills transfer and application and results in poor-quality hides and skins owing to poor handling, less professional workmanship and systemic wastages.

“The absence of industry process quality standards has led to the birth of private standards such as Leather Working Group, Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals, Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals, SEDEX and others to improve the environmental and ethical aspects in the leather sector,” said Nelson Agaba, a leather and textiles sustainability expert specialising in manufacturing, environment and social aspects.

Yet all is not lost. There are efforts, both by the private sector and governments, which will go a long way in growing the leather industry.

For instance, the one-stop Kinanie Leather Park in Athi River, Nairobi is nearing completion.

The Sh17 billion project, which had been hit by funding delays, is now 95 percent complete, according to Agriculture Cabinet Secretary (CS) Peter Munya.

The Kenya Leather Park (KLP), as it is called, sits on a 500-acre land that includes 14 tanneries and an effluent treatment plant. The CS said investors will enjoy incentives extended to those operating within the Export Processing Zone.

The other development is the launch last year of an online platform to boost leather across the region.

Leather Industry Network (LIN)-East Africa is billed as a one-stop-shop for traders in leather and leather products.

During the launch, Beatrice Mwasi, the director of the Centre for Business Innovation & Training-CBiT, said LIN (EA) will offer a reliable virtual space to connect, interact and transact business.

“The platform will serve as a one-stop-shop for information on the sector, including facts and statistics, as well as other quantitative measures for assessing, comparing and tracking performance and production,” she said.

Several interventions are, however, still necessary, especially as regards to quality infrastructure, if the potential of the leather industry in the region is to be fully unlocked.

What should be done

First, there is a need for a multi-stakeholder approach to ensure quality conformity in the entire value chain. A robust conformity and compliance monitoring system will spur confidence among consumers and regulators.

A relevant standard and certification scheme for various stages of the leather value chain will address the existing gaps in process standards. This should start at the farm level to ensure proper husbandry.

Slaughtering also needs to be better managed to ensure abattoirs are of the right standards and that slaughtering does not damage the skin. This extends to the construction of those abattoirs as well as preservation and transport of leather.

Secondly, harmonisation of standards will simplify the process of meeting requirements across the region and cut compliance costs while minimising conflicts and redundancies. This should extend to harmonisation of laws, policies and standards on environmental protection which is a major concern in the global leather business.

Thirdly, there is need to increase capacity of government institutions responsible for testing. This will enable more sensitisation and capacity building while increasing more testing labs accessible to the private sector.

Fourthly, adopting a traceable leather product labelling system will enhance accountability. This should go together with the adoption, and strict enforcement of, a ‘return, replace and repair’ mechanism to weed out inferior quality products.

The right inspection and proper grading and labelling in a way that all artisans can follow will guarantee consistency.

Sources of leather, tanning process and other parameters ought to be traceable to instill accountability and confidence in the region’s leather and leather product. The labeling system would not only be for traceability but also as a voluntary quality mark.

The hangtag in products like shoes should be more elaborate to include the product name, product standard number, specification (model), article number, main material (shell, lining) and qualification (inspection) mark.

In conclusion, a robust conformity and compliance system, harmonisation of standards, increased capacity of testing institutions and a traceable labelling system will raise quality and enhance intra-EAC trade in leather and leather products. This will awaken the sleeping giant, which is the leather industry in the region.